"Hell on wheels": the Edinburgh Trams Story

When Rishi Sunak cancelled HS2 at Conservative Conference, he announced the money would instead go on a wave of transport projects across the North. The most eye-catching announcement was a commitment to build a tram in Leeds - "famously, the largest city in Western Europe without a metro system".

It wasn't the only tram project announced either. The Network North document listed a number of other tram projects that could be funded as well – some of which hadn't already been built.

If we want to make a success of this new push on trams and change the fact that the average British tram project costs two and half times more than its French equivalent, then we should learn why past attempts have gone wrong.

Now, more people than ever are riding on Edinburgh’s trams, with passenger numbers doubling after the opening of the most recent extension. It provides easy access from the city’s suburbs and airport to the centre and takes pressure off the increasingly congested roads. There are even plans to further expand the tram to new regeneration and housing projects.

While it is now quite popular, it wasn’t always this way. During construction, the chairman of Edinburgh trams went so far as to describe the project as ‘hell on wheels’ in his resignation letter. Originally priced at £375m for 20 miles of tramway, it was significantly cut back to 8 ½ miles and the price exploded to £835m while also being delivered 5 years late. At a cost of £122m per mile adjusted for inflation, this puts it at three times the cost of the average French tram line (£43m) in Britain Remade’s Infrastructure Costs database. So why did this scheme go so far over budget and what can Britain do in the future to deliver much needed transport infrastructure? The findings from the Hardie inquiry, published last month, are a good place to start.

The TL;DR is:

The overseeing team had no experience managing a tram project;

The design provided to potential contractors was incomplete and changing;

The contract to re-route utilities was poorly managed and delayed;

Inexperienced negotiators allowed unchallenged price rises;

Mediation: a drawn out mediation process halted work and led to higher prices and cuts to the final length

Government oversight: Scottish ministers and Edinburgh Councillors failed to properly oversee the project and correct errors

But let’s dig in.

Experience

From the beginning the team tasked with delivering the trams faced pretty fundamental challenges. Transport Initiatives Edinburgh (Tie), the publicly-owned company that managed the construction of the tramline, had no corporate experience of delivering any major project. Most senior leaders lacked tram construction experience. While, the senior staff who were knowledgeable about building trams were often consultants rather than employees, which meant they had short notice periods and high turnover.

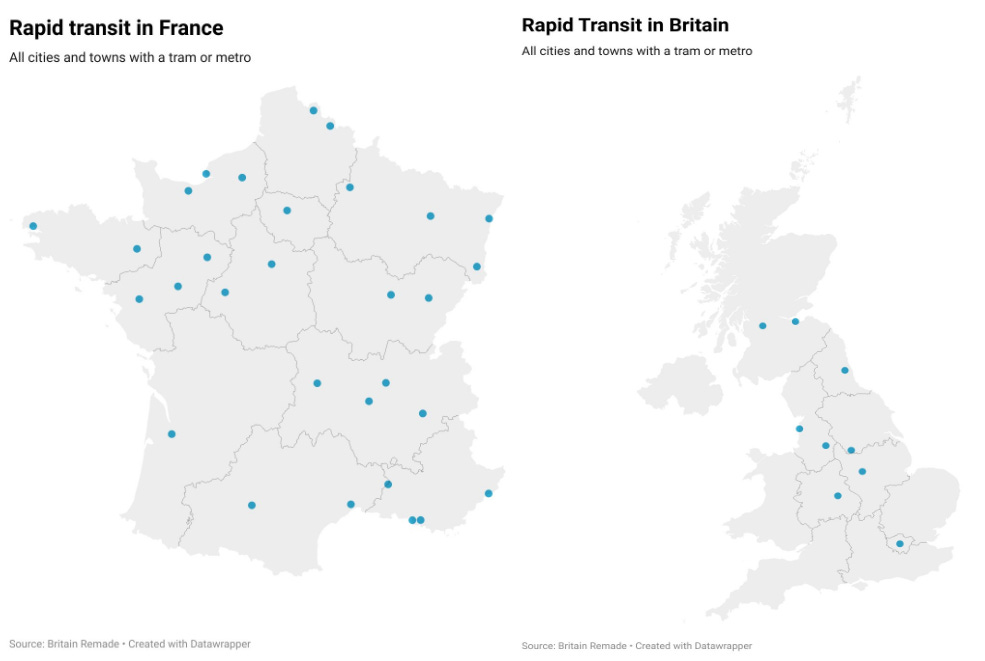

This is partly a problem for Britain as a whole, considering that we barely construct trams. While 30 French cities have trams, only 7 British cities do. France has managed to open tramlines in 21 cities since 2000. This means French project managers have a wealth of experience with building new tramways, while British management often learns painful lessons from scratch, and then forgets them before the next line is built.

Design

This fundamental lack of relevant tram experience cascaded into other problems. The tramline was designed by a private contractor who Tie failed to keep updated when there were changing requirements from the Scottish Parliament or the Edinburgh Councillors. Tie also failed to consult the latter two throughout the design process, which meant that the Councilors sent a massive number of comments late on in the process, creating further delays.

As a result of inexperience plus the chopping and changing of the plans for the tramway, information about the design provided to potential construction contractors was extremely poor, incomplete, and immature. Key details like junction design and planning approvals were missing. The design also continued to change throughout contract negotiations. As a result, contractors refused to specify a fixed final price and instead included large risk premiums.

Britain can learn design lessons from Italy, a country which constructs both tram and metro (underground rail) lines at around half the price of the UK. To avoid a situation where constant changes to the design pushes up costs, Italy has built up in-house expertise within its civil service capable of completing designs themselves. These civil servants are able to complete the final design in-house before it goes out for bidding, allowing contractors to have a better understanding of the scope of work, which means more accurate and cheaper bids.

The experienced civil servants can also replicate design elements between different projects, which drives standardisation and consistency for contractors who can then offer lower prices. Additionally to avoid delays to the planning approvals process, these civil servants convene a joint authorisation committee with representatives from all of the concerned authorities.

Utilities

The first step of actually constructing any tramline is re-routing the power, water, sewage, and other utilities that run underneath the road. In the case of Edinburgh, the location and extent of these utilities was not recorded, which meant construction companies added large risk premiums to their bids as there was a significant potential for unknown amounts of extra work. Tie tasked one supplier to remove almost all of the utilities, which was the largest such contract in Europe. They lacked the experience or skills to manage such a complex project.

To add to the misery, uncertainty around the 2007 Scottish Elections with the SNP originally promising to scrap the trams project, meant that the utility contract’s start was delayed. As a consequence, there was no buffer from when the utility clearing was scheduled to finish and when the tram construction was meant to begin. Of course, there were additional utilities found and unexpected underground obstructions leading to more delays. The contractor also signed off that they completed some sections, while there were still utilities present. These slippages were principally caused by the inability of Tie to manage its contractors.

The delays to utility clearing meant that when it came time to actually construct the tram line, contractors were not given access to the site because the utility work was still ongoing, leading to further delays and cost disputes. There was also an adversarial relationship forming between Tie and its contractors, leading to disputes and a costly mediation.

For French tram projects, utility diversion costs for private utilities like electricity, gas, and telephones are covered by the private owners of utilities. These private companies are the most capable of efficiently re-routing their cables and pipes because of their experience and incentives to do so cheaply. The private companies are encouraged to keep detailed records of their utilities, which limits the chances of unexpected delays for unknown utilities.

Contract Negotiation

When it came to negotiating contracts with the construction companies who would actually build the tramway, Tie’s lack of experience really came to the fore. In a deeply misguided attempt to control costs, Tie dispensed with having legal advice from an international law firm with infrastructure experience. This meant that there were significant periods of negotiations where Tie lacked any legal advice or relied solely on a junior solicitor who worked for them. If Tie had experienced legal advice, it is hard to imagine they would have committed so many serious errors in negotiation.

Due to concerns over delays, Tie was negotiating quickly, further weakening their hand. Key dates were moved forwards prematurely, such as the Notice of Intention to Award (NIA), which selects the preferred bidder. With a preferred bidder locked in, there is less competitive pressure, which means the contractor may start trying to raise prices. To counter this, there was a clause which meant the contractor would lose preferred bidder status if it did not adhere to terms, like including no further claims for additional payment. The contractor, a consortium of Bilfinger, Berger, and Siemens (BBS), then tested this by seeking increased prices. Tie did not use or even threaten to use the legal mechanism, which signalled to BBS that they could further inflate the price.

Over the course of striking the agreement and follow-ons there were delays in getting construction going, leading to more increases in cost. Tie did not have a proper understanding of the agreed contract, which meant that they were unable to properly challenge any requested changes or price increases. Ultimately this poor contract management meant that the contribution to Bilfinger’s profit and overhead swelled from 7.23% after the settlement agreement to 21.21% at the conclusion of the project.

Mediation

After the delays, cost overruns, and adversarial working relationship described above, Tie and its contractors were in dispute resolution for a large part of 2010 and work had effectively ceased. This eventually resulted in the parties entering into mediation in March 2011. Tie had two options: terminate and put the contract back out for tender or continue with the prior contractors.

The Hardie report describes Tie’s thinking through the mediation process:

“In the analysis undertaken in advance of mediation, the first of these options was substantially cheaper than the second, although there were uncertainties about the level of risk associated with re-procurement.

“On the eve of the mediation, £150 million was added to the estimated cost of the termination and re-procurement option. As a result, [Edinburgh’s councillors] preferred option of allowing [the contractor] to continue with the project was the cheaper option.

“No detailed support for the additional sum of £150 million was presented to the Inquiry… it is difficult to avoid the inference that its purpose was to provide a further justification for the acceptance of a mediation settlement that permitted [the contractor] to resume work on the project.”

The mediation resulted in an agreement of a settlement paid to the contractors, a higher fixed price, and cutting the line back from its original terminus at Newhaven to York Place in the city centre.

The Spanish show a different way is possible.

Spanish contract and dispute management provides important improvements to the way this process was handled. In the construction of 81 miles of underground for 9 times less per mile than the contemporaneous Jubilee line in London, the in-house programme managers created a system to effectively manage contractors. The goal was to build collaborative rather than adversarial relationships with contractors. By working with contractors instead of viewing them with suspicion, the Spanish foresaw problems earlier. They made a timely study of the most appropriate solution, and agreed the solution fairly with the contractor concerned. The overarching objective was to avoid disputes and reach agreements before the problems became unmanageable and led to work stoppages, like those that happened in Edinburgh.

Government Oversight

While tie was making a number of mistakes with the initial design, procurement, and contract management phase, there was a distinct lack of oversight from either Edinburgh’s councillors or from the Scottish government. Neither of these groups, which had ultimate responsibility for delivering the project, had external legal advice about the contract. Nor did they complete any review and quantification of the contract’s risks. Any safeguards in place to protect public finances were abandoned as both bodies took a scaled back approach.

***

The Hardie report makes it clear that there were a ‘litany of avoidable failures’ in the tram project. The upside is that the extension to Newhaven, which was dropped in mediation, has now been constructed to budget and on time, with ridership doubling. This is the clearest evidence that it is possible to learn lessons from failures and improve the process of building a tramway. Britain needs to learn these lessons and draw from the experience of other European countries that construct transit projects cheaper than us. If we do this, transport infrastructure costs will come down and we will be able to build more necessary links that connect Brits easier. However if we take the high cost of the initial Edinburgh tram project as a warning to not attempt to build transport projects, we will forget the lessons learned and be doomed to repeat them in the future.