Last week Britain Remade and Create Streets launched our report on where to build new towns and the design principles that will make them prosperous and liveable communities. In my previous post, I laid out why house prices compared to build costs should be the guiding principle in the placement of new towns in addition to rail connectivity, opportunities to mirror a town, space for 10,000+ new homes, and avoiding national landscapes, flood plains, and sites of special scientific interest.

We’ve applied those principles and have suggested the following new towns to the Government’s New Towns Taskforce. These 12 sites, conservatively, have room for over 550,000 homes and are expected to boost British GDP by £13bn-£28bn a year.

Greater Cambridge

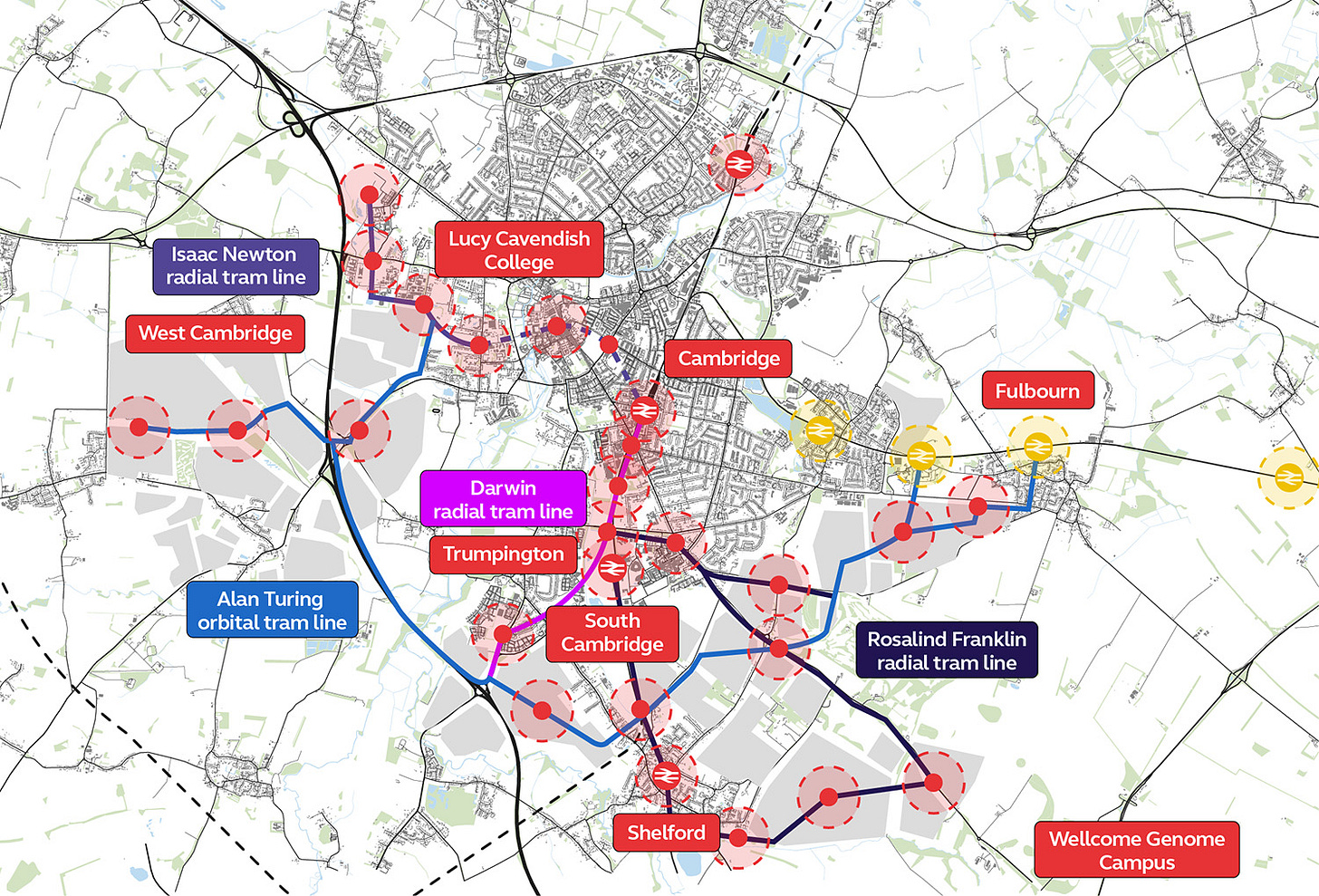

Cambridge has been a centre for scientific discovery for centuries. It is where the atom was first split and where the structure of DNA was discovered. Today the city has grown into Europe’s largest technology cluster, home to over 5,000 high tech firms, whose discoveries and inventions benefit all of the UK. Yet a lack of homes and new laboratory space is holding the city, and the country, back. Cambridge has the second most expensive housing of Britain’s large urban areas after London, pricing out many working people and young, bright researchers. The laboratory vacancy rate in Cambridge is just 1 per cent and Cambridge only has 1/10th the amount of laboratory space compared to Boston, an international rival. Additionally, while well-connected to inter-city destinations like London and Stansted Airport, intra-city travel within Cambridge is reliant on heavily congested roads and poor public transport.

A Greater Cambridge urban extension provides the solution to all of these problems. Building out the city provides space for at least 150,000 homes in mixed-use and beautiful neighbourhoods. There is well-placed land close to the soon-to-open Cambridge South Station near the Biomedical Campus and Addenbrooke’s hospital. Agricultural fields sit less than a mile west of the city centre, which would be suitable for walkable neighbourhoods. The railway line that passes through Fulbourn to the city's east could have several stations added to it. By allowing more people to live close to high productive jobs, these new homes would boost economic growth. The Ministry of Housing, Communities, and Local Government estimates that building these homes would add £6.4 billion to the UK’s economy and £1.5 billion of additional tax receipts.

At the same time these developments could unlock desperately-needed laboratory space. With a committed effort to build in Greater Cambridge, the new labs could become Europe’s answer to Silicon Valley. But if we fail to build, the advantages in academic power would go to waste.

Finally, a Greater Cambridge urban extension could be used to fund the transport upgrades that would make it easier to get to the many high quality jobs on offer and to see friends and family around the city. Every extra home built in Cambridge currently unlocks £235,000 in value uplift that can be spent on infrastructure upgrades. That is a massive amount of money that each new home creates that can be spent making Cambridge a great city. Assuming, very conservatively, that the true figure of value uplift is only half that (£118,000), and that we spend just 10 per cent of that on a tramway for Cambridge, then building 150,000 new homes would still unlock £1.75 billion. This is enough, at high British tram costs, to build a massive 20 mile network. If we were able to reduce British tram construction prices down to the European average, that could fund 42 miles. That large a network would completely revolutionise transport in Cambridge, boosting growth and accessibility. It could all be completely funded just by building new homes.

Tempsford, Bedfordshire

London, Oxford and Cambridge are the three British cities with the most acute housing crises, according to differences between house prices and estimated build costs. They also suffer from acute shortages of employment space, especially for laboratories. The reopening of East West Rail between Oxford and Cambridge offers a remarkable opportunity to alleviate all these shortages simultaneously. East West Rail will meet the East Coast Main Line near a hamlet called Tempsford. The interchange station there will enjoy excellent rail links to Cambridge (20 minutes) Oxford (1 hour), and central London (45 minutes), making it one of the best-connected greenfield sites in Europe. It is an ideal location for a new town.

The area is already benefiting from new infrastructure in the form of the A428 Black Cat to Caxton Gibbet improvement scheme. This unlocks the key infrastructure bottleneck holding back development of the site, giving it a good road connection to both Cambridge and Milton Keynes. It also has a good existing rail connection to central London on the recently-upgraded Thameslink, via nearby St Neots.

At the Budget, the Government confirmed plans to deliver East West Rail. The key infrastructure decision needed for Tempsford new town has thus already been made. Beyond this, improvements to the East Coast Main Line, especially around the Digswell Viaduct, can ensure plentiful rail capacity to London for any conceivable scale of development. (For more on Tempsford, and specifically the Digswell Viaduct bottleneck, see Dr Samuel Hughes and Kane Emerson’s excellent UKDayOne briefing).

Winslow, Buckinghamshire

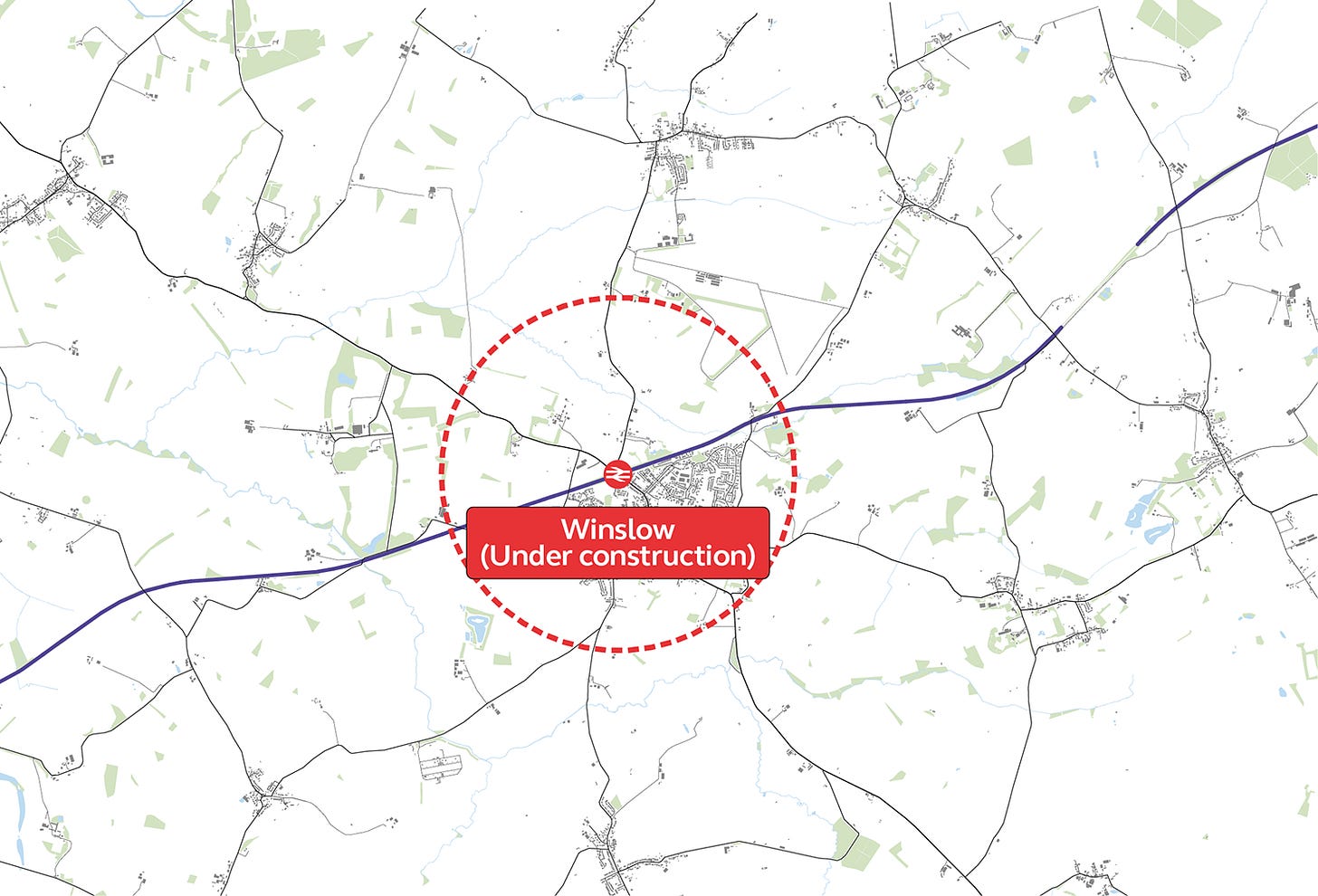

Next year the western section of East West Rail will open, which runs between Oxford and Bletchley/Milton Keynes. On the newly opened section of track there will be one completely new station, Winslow. Sitting on the northern outskirts of town, Winslow station will bring the railway back to the town for the first time in 57 years. Oxford will be less than half an hour on the train and the journey to Milton Keynes will be even shorter.

However, the issue is that the town will fail to fully realise the huge potential benefits that this boost in connectivity will bring because not enough people live near to the station. A Winslow new town would make the most of this historic railway investment.

The town of 4,400 sits almost completely to the southern side of the railway, allowing the town to ‘be completed’ by mirroring it on the other side of the tracks. Currently the land is non-green belt agricultural land. Conservatively estimated, there are 300-500 hectares of developable land within easy access of the station, providing enough land for a new town of 15,000 to 25,000 homes given a gentle density of 50 homes per hectare. Historic plans for supporting highways exist to assist further expansion.

These homes would be within walking distance of the station, allowing easy access to the high tech jobs of the future in Milton Keynes and Oxford, while preserving Winslow’s market town character. If the future branch of East West Rail is built between Winslow and Aylesbury Vale Parkway, Winslow new town would also benefit from easy access to London Marylebone.

Cheddington, Buckinghamshire

The West Coast Main Line (WCML), which runs from London to Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, and Glasgow is currently the busiest mixed-use railway in Europe and is effectively at capacity. But this will change when HS2 opens by 2033. By taking high speed intercity trains on to their own dedicated railway, HS2 will hugely reduce traffic on the WCML, opening up new commuter train capacity into London. To maximise the benefits of building one of the most expensive railways in the world, we should be building new homes and towns along the existing route of the WCML.

Many of the stations along the WCML are not surrounded by picturesque towns and villages that allow people easy access to the railway, but instead by the occasional car park and agricultural field. By choosing to build new homes within walking distance of these stations, we would be encouraging more environmentally friendly developments and benefiting from the extra capacity that HS2 brings.

Of all the stations on the route, Cheddington station provides perhaps the best opportunity to build a new town. Despite being just 50 minutes from Euston and on one of the busiest railway lines in Britain, Cheddington station is in the bottom 25 per cent of stations by passenger numbers. The reason for this is the railway station is over a kilometre outside of the village and is completely surrounded by fields, instead of the homes which would allow people to use the station freely.

However, these fields, which are not designated green belt, provide a perfect location for a gentle density new town fully to make use of the station and the extra services which HS2 will allow. There is enough land near the station to provide 25,000-50,000 homes at a gentle density of 50 homes per hectare. Cheddington’s easy access to both London and Milton Keynes makes it an attractive location for working people to easily reach jobs that match their skillset.

Cheddington is not the only location on the WCML capable of hosting more houses. It is only the nearest location to London with an existing station and a large supply of unrestricted land. However other locations, such as Roade in Northamptonshire or Wolverton, just north of Milton Keynes, are also viable. Closer to London, Tring is a possibility, though it would require the release of land from an AONB. The freeing up of capacity on the WCML is one of the greatest new town opportunities of our generation, and the Government should look at founding several towns along its length.

Salfords, Surrey

Brighton is the English city with the fourth worst housing crisis according to house prices compared to construction costs. Yet an urban extension of the city isn’t feasible because of the South Downs National Park that wraps around the city. Additionally trains from Brighton to London have to pass through the most congested and complex part of Britain’s rail network in the Croydon bottleneck, where 30 per cent more passengers and trains pass through each day than Euston and King’s Cross stations combined.

A new town along the Brighton Main Line provides an opportunity to relieve Brighton and London’s housing crisis, while also providing investment to fix the Croydon bottleneck and add an additional eight trains per hour. Considering that new homes in London create an average of around £285,000 of surplus value that can be used to invest in infrastructure, while homes in Brighton provide an average of £165,000, a new town along the Brighton Main Line would provide a significant opportunity to fund transport upgrades along the delay-prone railway line. Every thousand homes is potentially a quarter of a billion in additional investment into surrounding infrastructure.

Salfords, which lies about halfway between central London and Brighton, is the ideal location for this new town. The railway runs on the eastern outskirts of the village, providing an opportunity to mirror the town on the ‘wrong side of the tracks’. The missing half of the town means the station is not used as much as other ones a similar distance from London or Brighton. Despite its good connections, Salfords is in the bottom half of stations by use. A new town would see the station’s full potential used.

The new town would also be well served by existing roads. Just two and a half kilometres further east is the M23, where there is the potential to add in a new junction between Gatwick airport and the M25. Gatwick airport itself is just 5km south of the village, providing both jobs and international connections.

The land between Salfords station and the M23 provides roughly 750 to 1,500 developable hectares. At a gentle density of 50 homes per hectare, this is enough for between 37,500 to 75,000 new homes.

Greater Oxford

Oxford has been a centre for learning and invention for nearly a millennium. From the mass production of penicillin to the Oxford-AstraZeneca Covid-19 vaccine, the city has been a leader in biomedical advancements which have saved millions of lives around the world. Yet a lack of homes and laboratory space mean that Oxford, like Cambridge, is constrained in its ability to attract the world’s brightest talents and conduct advanced research.

Oxford has the third worst housing crisis among the UK’s 50 largest cities, pricing many early career researchers and working people from the productive jobs that the city has. The city has almost no available laboratory spaces for rent, threatening Britain’s ability to capitalise on its world-leading life sciences sector and forcing firms to move abroad.

While Oxford used to have an extensive tramway running along the wide streets in the centre of the city, now its roads are heavily congested. Travel around the city is reliant solely on buses or convoluted routes for cars. Every city in France over 150,000 people has a tramway, Oxford (population 165,000) should be no different.

Countries across the globe are desperate to have world-leading universities like Oxford and Cambridge, yet Britain has them and fails to let their cities grow to maximise the benefits. A Greater Oxford is essential to accelerating scientific and technological advancement through expanded laboratory space, while providing the homes for the researchers and workers who will build this future.

There are several growth areas around Oxford that can accommodate these new homes and laboratory spaces. These broadly fit within an arc from Oxford’s north around its western edge and then along the railway line to the south of the city.

Oxford Parkway station opened in 2015 and is just six minutes from central Oxford. Yet it is surrounded by a large surface parking lot, a golf course, and some fields. There are plans to build up to 800 homes nearby on 46 hectares of land, but at just 17 homes per hectare this development will fail to deliver as many homes as a gentle density approach on the same amount of land. Even taking into account this planned development, there are still 100-200 hectares of land that is within an easy walk of the station, which would be best used to build part of an Oxford urban extension.

Plans for a station at Begbroke to Oxford’s north have been proposed for the better part of a decade by Network Rail and Cherwell District Council. A station here would provide easy access to Oxford’s centre while also providing the opportunity to build new homes through an expansion of Kidlington.

The best opportunity to directly extend Oxford is along the western side of the city. Although there are constraints around Sites of Special Scientific Interest and flood plains, there is still significant land to build the new homes and laboratory spaces that Oxford desperately needs. The area south of Botley towards South Hinksey is the most promising due to its proximity to the city centre and to the ring road. The development could help fund a tramway for Oxford, relieving pressure on the congested roads into the city centre.

Finally, new development should also be considered south along the railway out of Oxford at Culham. Culham Science Centre is a world-leading cluster for fusion energy research and development built next to Culham railway station. By improving the rail links between Didcot and central Oxford from the existing hourly service, there is large potential to unlock the land surrounding the station and near the science centre for new homes and communities.

Iver, Buckinghamshire

The Elizabeth Line has been a massive success and is the UK’s busiest railway; already one in every six national rail journeys is on the line. Yet there are several stations on the western end of the route which have significant land adjacent to them that could be developed into well-connected new towns.

Iver and its neighbouring station, Langley, are just half an hour from central London. Yet instead of being surrounded by homes that allow people to make the most of this fantastic link, they are bordered by low density industrial land and fields. With the significant investment of £19bn that has gone into the Elizabeth Line, we should want people to be able to live close to its stations.

There are approximately 400-600 hectares of land on the north side and part of the south side of the tracks that could be developed into a new town. At a gentle density of 50 homes per hectare, that would be sufficient land for 20,000-30,000 new homes with fantastic access to all the amenities and well-paying jobs that London has to offer.

The area also benefits from its proximity to the M25, M4, and Heathrow Airport. It would be especially suitable if the Heathrow Western Rail Link goes ahead, which would provide non-stop access to the airport from Langley station.

Hatfield Peverel, Essex

The Elizabeth Line opening has increased capacity at Liverpool Street Station as services from Shenfield no longer terminate at the station and instead go through central London. With a few infrastructure upgrades, such as remodelling Bow Junction and adding passing loops on the line between Chelmsford and Colchester, additional stopping services could be added on the Great Eastern Main Line (GEML). This extra capacity could be used to provide more services to Hatfield Peverel, the best location for a new town in Essex.

Hatfield Peverel is less than 45 minutes from Liverpool Street and the station itself is completely to the north of the village. On the other side of the tracks, within walking distance of the station, there is non-green belt agricultural land, providing ample opportunity to build a new gentle density community. There are approximately 300-500 hectares of developable land within easy access to the station. This is enough for 15,000-25,000 homes.

Hatfield Peverel is also well-connected to the strategic road network. The A12 runs through the village, one of the busiest roads in the east of England, providing the main link between Ipswich, Colchester, Chelmsford and London. A plan to upgrade the road was given planning permission earlier this year after submitting 58,000 pages of paperwork and overcoming a judicial review. Yet this scheme, like many other road and rail projects, is going through a review as part of the forthcoming infrastructure plan. The demand that the new town generates and added funding that could come from the land value uplift from the new homes could help make the road upgrade viable, improving the lives of motorists across the East of England.

While Hatfield Peverel provides the best combination of proximity to London and size of developable area, there are similar opportunities to build new towns along the GEML at Marks Tey, Kelvedon, and Ingatestone. The latter could even be served by a short extension of the Elizabeth line considering its proximity to the current terminus of Shenfield.

Bristol Extension

Bristol has Britain’s worst housing crisis outside of the greater south east of England. The median home in Bristol now costs around 10 times the median income, which means Bristol’s homes are the least affordable of any of Britain’s large regional cities. This housing crisis is in part caused by one of the most restrictive green belts in the UK. The green belt is 4.5 times larger than Bristol itself and it is less than two miles from Bristol Temple Meads station to green belt land in multiple directions, effectively choking off Bristol’s potential.

There are several options to expand Bristol that should be considered alongside any densification plans.

There are plans to build an urban extension to Bristol’s north east near the village of Pucklechurch alongside an extension at Lyde Green, which has just finished construction. This area is well-connected to Bristol’s roads, being near the M4 and A4174 orbital road, and with the option of a new motorway junction. Yet it is not well-connected to transit. Building an extension to Bristol could fund a long-desired tram in Bristol. Assuming 50,000 homes are built across the Bristol urban area and construction costs are £90,000 less than sale price as they are now, up to £4.5bn of surplus value could be unlocked. Just 20 per cent of this would be enough to give Bristol a 21 mile tram network if construction costs were brought down to the European average.

Pilning Station is among the least used 1 per cent of stations, with only 338 passengers getting on or off a train there last year. The station itself is less than 20 minutes from Bristol Temple Meads and development around the station would encourage a more regular service than the very limited two trains per week parliamentary service that exists now. While a lot of the land around the station is flood plain, the severity of Bristol’s housing crisis could enable funding of flood defences for a development surrounding the station.

Plans to undo the Beeching cut and reopen the railway line to Portishead from Bristol has received planning permission. Despite only needing to rebuild 3.3 miles of track, the planning application was 79,187 pages (or 14.6 miles if printed out and laid end to end). Now the line is awaiting judgement as part of the infrastructure review launched after the scrapping of the Restoring Your Railway programme. Without funding, which could be provided from the uplift of homebuilding, the line will be scraped. There are approximately 150-200 hectares of developable land near the potentially restored railway that could be developed to help fund the project and relieve Bristol’s housing crisis.

Chippenham, Wiltshire

Historically a small market town built around a crossing point of the River Avon, Chippenham is conveniently located on the main line between London and Bristol Temple Meads. The town grew significantly in the post-war period which saw an increasing number of large developments expand into the surrounding countryside, supported by a network of A-Roads and roundabouts. The town has long been earmarked for expansion, but continuing this pattern of unsustainable sprawl is neither desirable nor viable. A previous plan, dependent on public funding of at least £75 million for a new distributor road, would have delivered up to 7,500 homes. This was cut back to 4,500, before being scrapped entirely in the face of local opposition.

Create Streets, working alongside Sustrans, have developed an alternative proposal for expansion using a ‘vision-led’ approach to transport and planning, investing in quality of place and a suite of sustainable transport solutions, rather than solely relying on unsustainable and expensive road infrastructure. The aim would be to create a contiguous urban extension, rather than a series of car dependent housing developments hung off the ring road, resulting in happier, healthier, more productive and sustainable places. The resulting ‘gentle density’ plan is for a walkable, well-connected and integrated town extension with good air quality, less congestion and vibrant neighbourhoods. The plan shows how the same number of homes can be delivered as the sprawling road-led scheme, within the same budget, and with far less land take.

Under this ‘gentle density’ plan, Chippenham would extend organically out to the east of the town centre, providing up to 10,000 new homes. Residents would be able to walk 20 minutes to reach the train station and high street, which is far closer than the previous proposed expansion to the south. Schools, nurseries and convenience shops will be nestled within the new development, while terraced homes and mansion blocks will provide more homes close to its centre.

The £75 million that was allocated for road infrastructure would instead be invested in a range of interventions to help improve the quality of place, tackle pollution and keep people moving. These include increasing the frequency of the north south TransWilts line connecting Melksham, Swindon and Trowbridge. Services would increase to at least one train per hour from the current one train every two hours, thanks to the delivery of a new passing loop to the south of the town for a modest investment of £15 million. A new service to Oxford is currently being trialled at the weekends, and this could be made permanent if new development justifies it. Together, these improvements would make commuting by rail a viable and attractive alternative to driving. Segregated and shared cycle lanes throughout will allow new and existing residents to safely make their way to school, the shops or to simply see friends on the other side of town. For those unable to cycle, Chippenham’s 2016 public transport strategy will be funded to provide a high-quality bus service within the town.

These improvements would benefit both future and existing residents of the town, encouraging a move from car dependency to reliance on a wider range of transport options. Investment would also be directed to the historic town centre to improve the local high street, historic buildings and the public realm, to pull people back into the town centre and help it thrive.

Overall, a vision led approach to planning combined with a ‘gentle density’ approach to design and placemaking, will result in more homes on less land and support happier, healthier and more prosperous towns.

York

Since Roman times, York has been defended, and defined, by walls. Yet it is no longer the mediaeval walls that constrain how York can grow, but York’s green belt, which is among the most restrictive in England. You can walk from the Shambles, in the city centre, to the green belt in less than a mile. The centre of York faces challenges between balancing new homes, new student accommodation, places for tourists, and businesses wanting to expand in the highly educated and well-connected city.

As a result of this lack of developable land, homes in York are among the most expensive across the North. The median home here costs £80,000 more than the cost of building, providing a large uplift that can be used for infrastructure improvements and more social housing.

York is surrounded by a ring road that is approximately five miles in diameter. But the city itself does not stretch to meet the ring road. Instead the ring road travels directly through York’s green belt. The city should be allowed to extend to its ring road. Given the rising cost of housing in York, which prices many students and workers out, there is clearly demand to live in the beautiful city. The existing York Outer Ring Road improvements, which received planning permission in April, mean that there will be significant new transport capacity in the area.

In France, every city with a population greater than 150,000 has a tram. York has a population of just over 200,000 people but it goes without mass transit. An expansion of York to encompass its ring road would enable the funding of a tramway to make it easier to get in and around the city. A 10 mile tramway system could be funded by just 25 per cent of the surplus value of 20,000 homes if built at the European average cost. The funding could also deliver proposed improvements to the A64 Hopgrove roundabout, increasing access to the countryside and towns to the east.

The city would still remain compact and relatively small, only extending up to three miles from the historic centre. York is a reasonably flat city, so a network of high quality cycle routes could allow most people to cycle into the centre in 15 to 20 minutes. This could easily be funded by capturing just a small proportion of the vale uplift from the new housing it would unlock.

Within any York extension plans, there should be a priority to build around Poppleton station. With trains that take only five minutes to access the city centre and the Poppleton Park and Ride along one of the main routes into York, the area is well-connected. Currently, however, the station is in the bottom third of stations by use, because the green belt has limited new homes from being built nearby that could make use of the station’s connectivity. The value uplift from the new town could fund the electrification of the Harrogate line that Poppleton is on, providing faster, greener, and more reliable rail service between Leeds, Harrogate, and York.

Situated at the junction between the A59 and the Leeds ring road, Poppleton has good road connections and will partially benefit from the York Outer Ring Road (YORR) scheme. Yet the YORR will not be dualling the stretches nearest Poppleton due to a lack of funding for new bridges over the River Ouse and East Coast Main Line. This is a problem that part of the uplift from the new town could rectify.

Expanding York to its ring road and building around Poppleton station could provide York with 50,000-75,000 new homes based on developable areas within the ring road at a gross density of 30 to 50 homes per hectare. This will help to boost housing affordability and let more people live near the employment and educational opportunities that the city provides. Plus these new homes could bring trams back to York’s streets for the first time in 90 years.

Arden Cross (Birmingham Interchange)

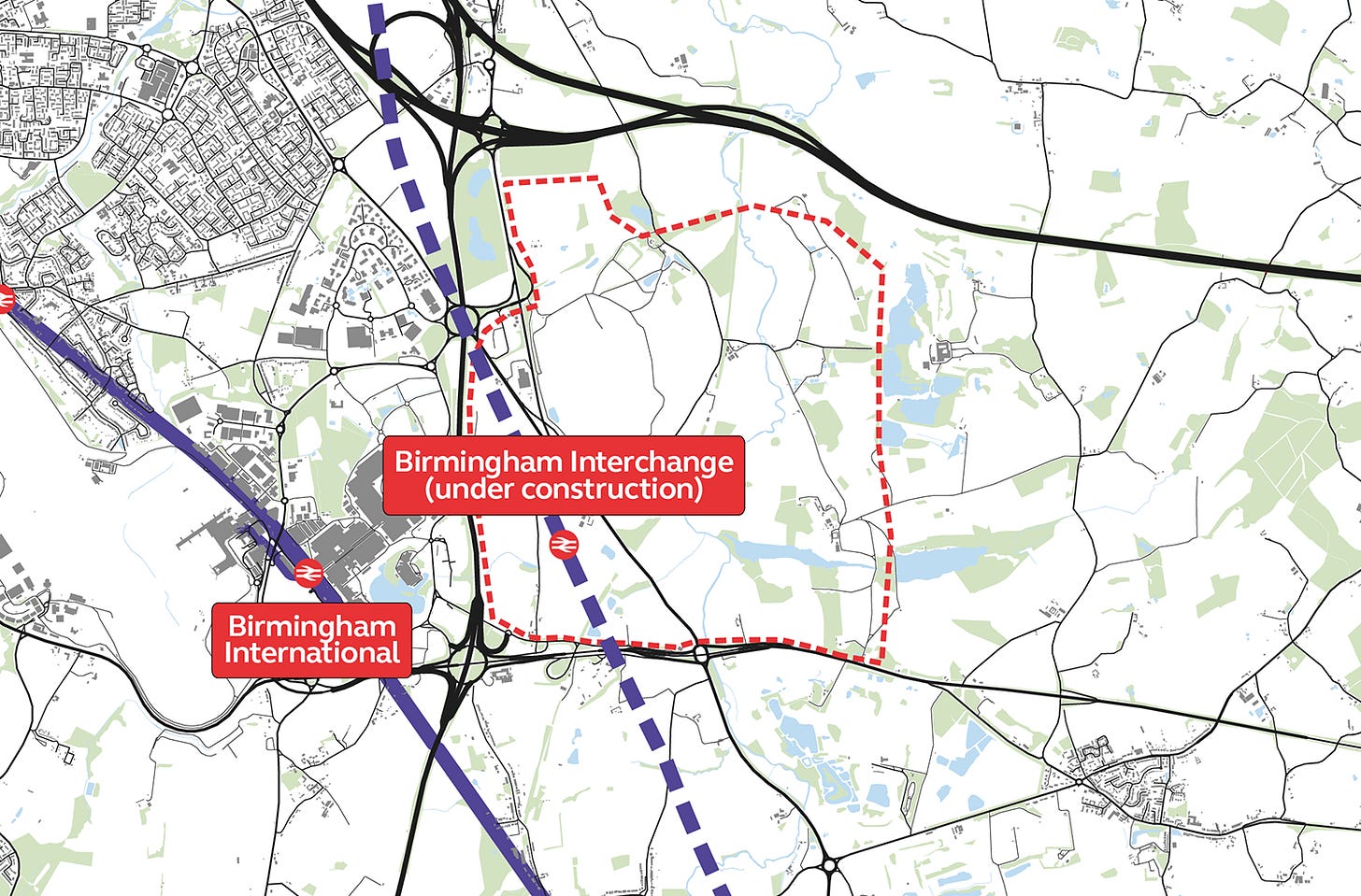

One of the largest infrastructure investments in the UK is currently taking place in a field in the West Midlands green belt. Birmingham Interchange station will be the lynchpin of HS2 services, being the only station outside of London through which all HS2 services must pass.

Currently, a medium-sized development of 3,000 houses is planned next to the station. However, the site will stretch no further than the HS2 station car park. By the simple expedient of crossing a road, a site ten times larger becomes available. This is enough for a genuine town - a community large enough to have its own identity and to contribute to the vitality and character of the West Midlands conurbation.

Even without HS2, the site is remarkably well-connected: it is less than a mile to Birmingham International station, Birmingham airport, a newly upgraded motorway junction on the M42 and the A45, the principal route from Coventry to Birmingham. A Birmingham to Solihull metro extension has been proposed, which will run to the Interchange station, yet it currently lacks funding. A new town here could provide the necessary funds for the extension, which will benefit East Birmingham and Solihull. All that is needed would be an extra stop beyond the Interchange station to run to Arden Cross’s centre. This could even be delivered along an existing, disused railway that crosses the site. Action now would allow passive provision for the link without disrupting the operations of HS2.

A new community at Arden Cross, next to the HS2 station, can deliver this potential. The attractiveness of the location as a place for office and retail development is extremely high, making it a place that can sustain a strong local economy based on its fundamental advantages.

This site has historically been kept from development by the existence of the Green Belt, and the wish to keep Coventry and Birmingham from becoming a contiguous urban area. This same goal can be achieved by the creation of a large green reserve, while releasing the land that is the best-connected location in the Midlands.

Conclusion

New towns could play a key role for solving Britain’s housing shortage if they are planned and located well with fast-track planning through Acts of Parliament. Create Streets and Britain Remade’s new report Creating New Towns Fast and Well provides the framework and suggested locations to make new towns prosperous and liveable communities.

Thank you for reading and I wish you a Happy Christmas and New Year!

You are tripping on something if you consider 50 homes per hectare, which amounts to 32000 people per square mile, to be "gentle".

Dear Ben,

I am writing to you via Yes and Grow as I am finding it difficult to contact Britain Remade by email.

Could you email me and I can send you a two-page summary of a proposal that provides answers to the questions raised by yourselves and reported by Rosa Silver in today's Daily Telegraph.

Yours,

tony@tonynordberg.com